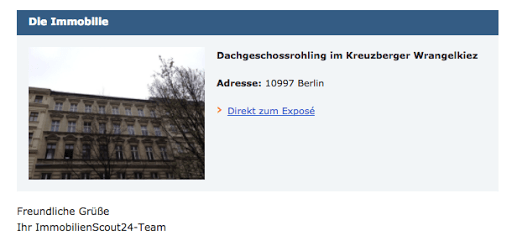

I’m in the process of creating somewhere to live.

My thinking about building strong teams

My work goal is:

So I started thinking about how I like to guide teams.

I’ve had smart people on teams that I’ve run. I mean really smart, equipped with deep subject knowledge. These developers that were leagues ahead of others on the team. They wrote close to perfect code. They were also great at working directly with me and terrible at working with the rest of the team.

In one particular case, the individual contributor wasn’t able to, even after my working directly with him and my working with the rest of the team, to integrate. And even though he was a star contributor, I had to let him go.

Teams are greater than the sum of their parts. It was sad to see him go. But also relieving for other members on the team who felt uncomfortable with the situation. Development work is the antithesis of working on a production like: we crave the interaction, the learning from other experts sitting next to us (and everyone is an expert in something). But someone unable to share their knowledge with others can only last so long in a team, and in this case was risking a team rift and the future of the project.

None of this development stuff is rocket science. As technologists, we’re excited by the exotic, the new, the big “I deployed 1000 servers in 5 minutes” chest beating. But when you peer behind the curtain and stick around for long enough you notice the same patterns repeating again and again. The exotic was Java, then Ruby, Node, and now it’s Go. All great languages. All accompanied by the familiar aura of newness-hype.

Hype cycles come and go: it’s too easy to jump onto trends. Now it’s micro-services. Next week there will be a new hype rocket leaving earth. We like the hype because it’s something to learn and the best people in IT are self-learners. The hyped-newness takes us deeper into our craft. The hype touches our curiosity-gland and new phrases make it sound exotic.

I’m not dissing container technology or a micro-service approach, I am pointing out that there are always new trends on the technology event-horizon. We flirt with them (full disclaimer: I’m a huge new technology flirt). We kick the tires, try out a deployment or project with them.

A good team solves problems with great code and suns a smooth service. But our attraction to the new can blinker our vision: we serve our users not our tools and technology. Our users want solutions to their problems: “excite my ears with your streaming music” and “keep me happy with a mobile app that starts quickly”. That mobile app starts quickly because we were careful choosing our technology: sifting the value from the hype.

In the business world we see a similar things happening: in-sourcing is the new near-sourcing that once was outsourcing. Trends come and go.

When thinking about which trends to ride I imagine the selection to be somewhat similar to a hobo hopping trains to reach a destination. Hop the wrong train and your next stop is 80 miles down the track in the wrong direction. The observant hobo will discern which trains head out in the right direction and ride them until they veer off course.

So when we start feeling that our work is rocket science, it’s usually a sign to refocus and remember that even rocket scientists are practising a craft. And while we aren’t returning astronauts safely back to the earth, we are solving problems for our users who frankly don’t give a damn about tech hype.

I’m very much in favour of experimenting with the hyped-newness: it’s how we learn our craft, it’s how we experiment with new tools, and how we decide which technology trains to hop.

Summary:

I have a decision making system “gut-data-gut”:

Sometimes it takes a while to get a good/bad feeling about a decision. For example, imagine we’re a team thinking about what container system to use. This is a big decision that will impact the entire team. And yet, unless someone on the team has extensive experience, we need to hold off committing to something big until we can build up a strong team consensus.

But not making a decision will also slow us down. Or will it? Usually there’s another way: delay the decision until you really have all the gut-data, and the data-data. This sounds like a cop-out but if I can explain: In our example, not knowing what container format to use we can’t progress.

It turns out that this decision can be delayed while we look at some of the tooling options available for orchestrating the containers. And the decision can be delayed even further while we start building our new tooling (assuming that the orchestration system supports the different container types). All these other tasks touch on our container format decision and help to indirectly inform us.

Now we have our data-data and our gut-data and can make a strong decision and progress.

There’s a thousand books about running teams and setting goals each explaining a different way to work with people.

Mine’s pretty simple: be nice to each other and good things will happen. Be nice means listening, questioning and treating each other’s egos with care / remembering that we all have insecurities. Shifting slightly to the right of the Kumbaya campfire, teams need to get stuff done: solving problems.

And that’s precisely how I like to run a team: frame the problem. When we know what the problem to be solved is, our engineering minds naturally start working toward a solution. The trick is asking the right question to discover the real problem. Using the previous example: is the real problem which container solution to use or is the real problem how to run a smooth service?

Without getting too meta, good teams come from hiring people smarter than myself. Usually much more so! Some of my best teams have been where I’ve felt like the stupidest person in the room. And yet I’ve felt valued because I had other skills to contribute. I wouldn’t be the deepest in the tech stack. I would feel comfortable that others knew what they were doing there. But I was able to clear the path so that the team could get stuff done without the organisation getting in the way. Some might call this managing up the organisation. And since the team knows what the problem is, they can now solve it without the weight of an organisation slowing them down.

This example of being the stupidest on the team (sure there’s a nicer way to say this but let’s press on), also illustrates the need for diversity in a team. There’s always going to be stronger candidates. And weaker candidates. But each has their role: I’ve seen strong candidates mentoring newer candidates. And I’ve seen newer candidates digging into documentation and meticulously fixing examples that would be missed by our flag-waving strong candidate. The trick is to develop a mutual respect in the team for everyone’s skills.

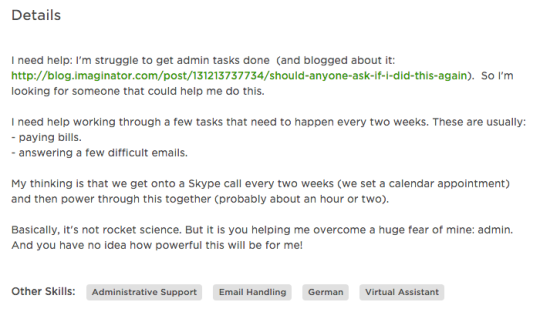

A few weeks ago I was hitting the admin wall: many small tasks that needed doing. Many small tasks that were turning into mountains. Many small tasks that were taking up space in my brain.

I admitted to myself:

To solve this problem I started looking for a virtual assistant on Upwork.

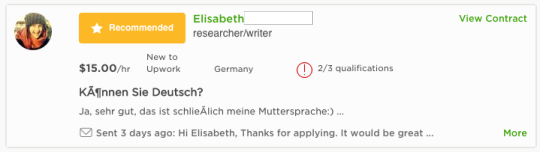

I needed someone that could also help me while working both in English and in German. I received 5 applications from as far afield as Vancouver and Australia. One Applicant was Elisabeth. From Berlin too!

I dislike personnel administration: time zone differences from working with far off places would mean I’d be also sacrificing my nights to the beast. Vancouver and Australia were out and I hired Elisabeth. Having someone in Berlin with the option to potentially meetup seemed like a good option. I went ahead and arranged an initial Google Hangout call with Elisabeth.

While I was waiting for the hangout call, I setup a Trello board and started dumping all my admin tasks onto a to-do list. And basked in the warm GTD feeling of getting things out of my head and onto a list.

This week started with my first session with Elisabeth. 9am and a strong coffee and knowing that I had support were powerful motivators for getting into the office! We powered through the tasks together: she doing some of them, me the rest: it was so much easier working this way. Yes, it took two hours, but that was a lot of build-up. I expect the next session to be about 30 minutes.

Without thinking too much about where this fear/hate/loathing of admin tasks comes from, I feel much better for knowing that a bunch of them are done.

Perhaps not perfectly. But done!

Wanna do the same? Here’s the “I hate admin” summary plan if you want to setup a system like mine:

Do great things without admin hanging over you!

I’m petrified of heights. I love rock climbing.

Being on the climbing wall wakes up primal fears. All I can focus on is staying on the wall. No work thoughts. No relationship thoughts. Just facing one fear. Slowly working up the wall to the top.

Climbing routes are marked out with a difficulty. For example one of the routes I climbed yesterday, marked as a 5+ difficulty, meant that I was only using the purple grips. The routes are cleverly designed: there’s always a way to the top. The routes gets increasingly more difficult as the numbers rise.

The grips on the wall are placed so that you’re solving a puzzle with a combination of two hands, two feet and your body weight. Half way up I’ll hit a patch that looks like there is no way forward. The grips above me are too high and the grip that I’m standing on is awkwardly placed. I’ll try and reach for the grip in front but it’s too far and I risk falling. Then I discover the grip I’d overlooked by my right foot because it’s out to the side. By shifting my weight to a new foothold I can better reach the grips above my head and suddenly a new route opens up and I can progress higher on the wall.

Climbing shows us how different perspectives on a problem impact how we feel about it and solve it. For example, when watching a partner climb, we have a very different perspective and feeling.

Perspective-wise, we can see a different route up the wall from our firmly-on-the-ground viewpoint. Feeling-wise, it’s easy to suggest “just reach for it” from below. And yet this is so different to being on the wall yourself.

From below you see a different route up: different because you can see different footholds or grips that they can’t see. Different because your vision isn’t clouded by fear or the pain in your arms when getting around an overhang.

Hearing “there’s a grip to your left that might help” is useful. Being able to jump over our fear of falling in case we can’t reach the grip is hard. And needing to trust our climbing partner to be securing well in case of a fall, even harder.

Another thing I like about rock climbing: it teaches me the value of taking a break. Apart from good upper body strength, I imagine good climbers are intimately acquainted with their their own limits: how far they can reach, how long they can hang on in overhang or how long they can remain stretched out before the next push. Good climbers know when to take a break, when to hang on the wall with all your weight on the rope, resting the arms, recharging (and re-chalking). I’m not good at taking breaks. On the wall or in life. This year I have taken one week off (and stayed in the city). It’s a lousy way to progress and I’m not proud of it. I have a lovely break planned for the end of the year. If I can get there without falling from the wall. I’d like to change this approach in 2016. Know that I will need breaks and pre-plan them into the work year.

As a child I loved climbing trees. But I also had a healthy respect for the heights. Rock climbing reminds me of this flirting with fear and I love the “fear focus” that blocks out all the “brain noise” as you reach for the next grip.

If you are in Berlin and fancy learning, I think I’m a pretty good teacher.

I was 19 years old and walking from my London apartment on Gunterstone Road to Hyde Park. It was a sunny Saturday, there were many people on Kensington High Street. I had finished high school, was working at a publishing company during my gap year, and that day, walking along and thinking about how I wanted my future life to be (yes, even back then I was a personal-development geek). Living in a big city like London was something new to me. After growing up in a small suburb in South Africa, London was different. Very different.

In trying to make sense of these differences, I remember being concerned that the lowest common denominator seemed to win out in many city planning decisions. Looking around me I’d notice that the city didn’t work perfectly. Lights weren’t perfectly synchronised. Sometimes trains ran late. It seemed to me like things could be better, but good enough sufficed.

I’d grown up with the idea that “the UK was first-world and therefore got everything right, South Africa was third world and was imperfect”. This magical far off country wasn’t struggling with the violence, poverty and racial divide of South Africa. This tinted view was serenely delivered to darkest Africa on Sunday evenings via a radio in my father’s woodworking shop. Anthony Lejourn’s London Letter would paint a wistful picture of the perfect life in the “motherland” as my father showed me how to build things from wood.

I was trying to make sense of my relationship with London: why was it that things didn’t work perfectly, especially if this was the perfect city? This was also the stage in my life where I’d put a new girlfriend on a pedestal and admire her perfection until friction exposed imperfection.

Today I can look back at that time and realise that labelling anything perfect, be it the admired girlfriend on the pedestal or the first world city, dooms me to disappointment. There is always a chink in the armour, always the moment when, perfect vanishes never to return. That moment when perfect is closer to really nice. I live in Berlin now. It’s really nice. Certainly not perfect. But right for the moment.

And so to the idea of gratitude: I’m asking myself why I’ve never been a fan of the gratitude. My gut immediately feels like it’s fake. I can see the value, but in the back of my mind there’s been a “yes, but”. The subtext being “Yes you can be grateful for that, but don’t you see this problem” or expanded even more “…but don’t you see the imperfection in that corner”. It’s a heavy load to carry.

And yet this is the same “she’s perfect”, “London’s perfect” thinking that never worked out in the past. The power to be grateful for the really nice or even the imperfect is a very powerful skill and echoes the vibrant positive personalities I see in many of my happiest friends.

Gratitude exercises can feel like checking off a list. Yeah, health, no war, warm clothes, roof above the head. Grateful, grateful, grateful, check check. And now? It sometimes feels like lowering my standards. Like not striving anymore. No more perfection. Here’s your mediocre served under a dry roof. And so we’re back to the perfect becoming the enemy of the really nice. And that didn’t work out so well in the past.

I have much to be grateful for. There are chinks of imperfection. And some chunks of major imperfection.

But my life is good. And should anyone ask, this is me dipping my toe in the gratitude waters:

I’m grateful for the people and memories that have come into my life. And for the moments when I can smile. (Like this photo from back then. Boy I was young! And happy.)