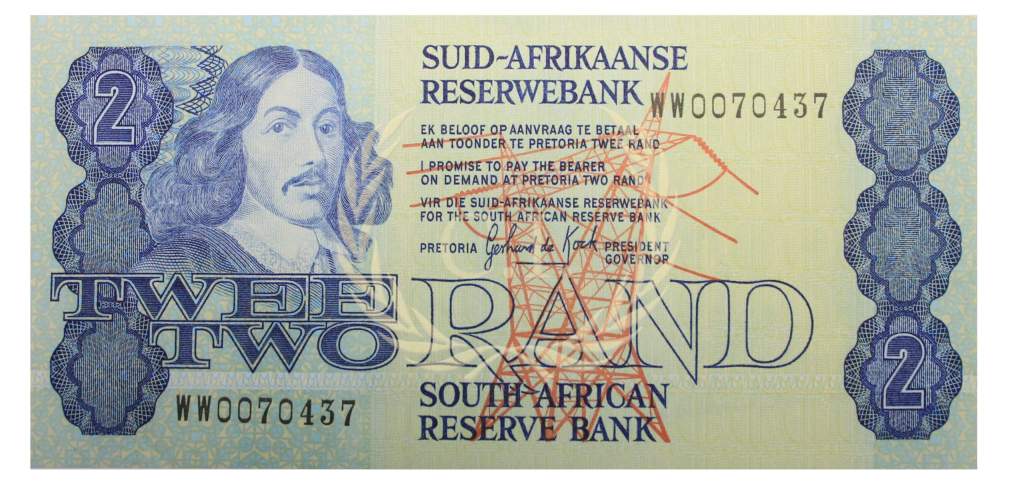

The picture above is the South African R2 (Rand) note. It was my monthly pocket money. As a kid it felt like a lot of money. Indeed it would have afforded me 200 chappies (bubble gum). Or a few bottles of Coke.

That R2 is now it’s worth about $0.08.

I remember asking my mother about the line “I promise to pay the bearer on demand at Pretoria (where the central bank is) two Rand”. Promises sounded serious and someone was going to pay me. That line had the attention of 8 year old Simon! Could we drive to Pretoria and find out? My mother (incorrectly) explained that you could go to the central bank and exchange the R2 for a small amount of gold. This was certainly no longer the case since South Africa had left the gold standard in 1932. Curiously this line was left on notes to create the symbolic assurance of value. South Africa was by no means unique: many other post gold standard countries had similar wording. It speaks to the times of needing to create assurance.

Then I took the R2 note to my father and asking about redeeming it for gold, where the gold was stored and when we could begin the 6 hour drive to Pretoria? My father, being more the sceptic, informed me that the central bank was no longer handing out gold. My question was then, if we don’t get gold for this money then it’s worthless paper. “Not so!” and so began one of many economics lectures: The value of my R2 came from how often it was used to buy things (velocity of money 101). This led to other lessons on inflation: “we need inflation because the economy grows and therefore we need more money.” Also, “inflation stimulates the economy”. Looking back it’s interesting to see the strong influence of Keynesian economics on my father. He would have loved Bitcoin.

Looking back at this R2 note, I find the choice of an electricity pylon interesting. This was the time of a national electrification rollout and the construction of South African’s first (and only) nuclear power plant.

The R2 note back is more interesting: the Sasol coal to fuel plant and reflected South Africa in the 1980s: isolated by sanctions the big fear was of an oil embargo. But the country had abundant coal reserves and developed an innovative method to convert coal to synthetic fuel. Not needing to import oil also helped preserve dwindling foreign exchange assets.

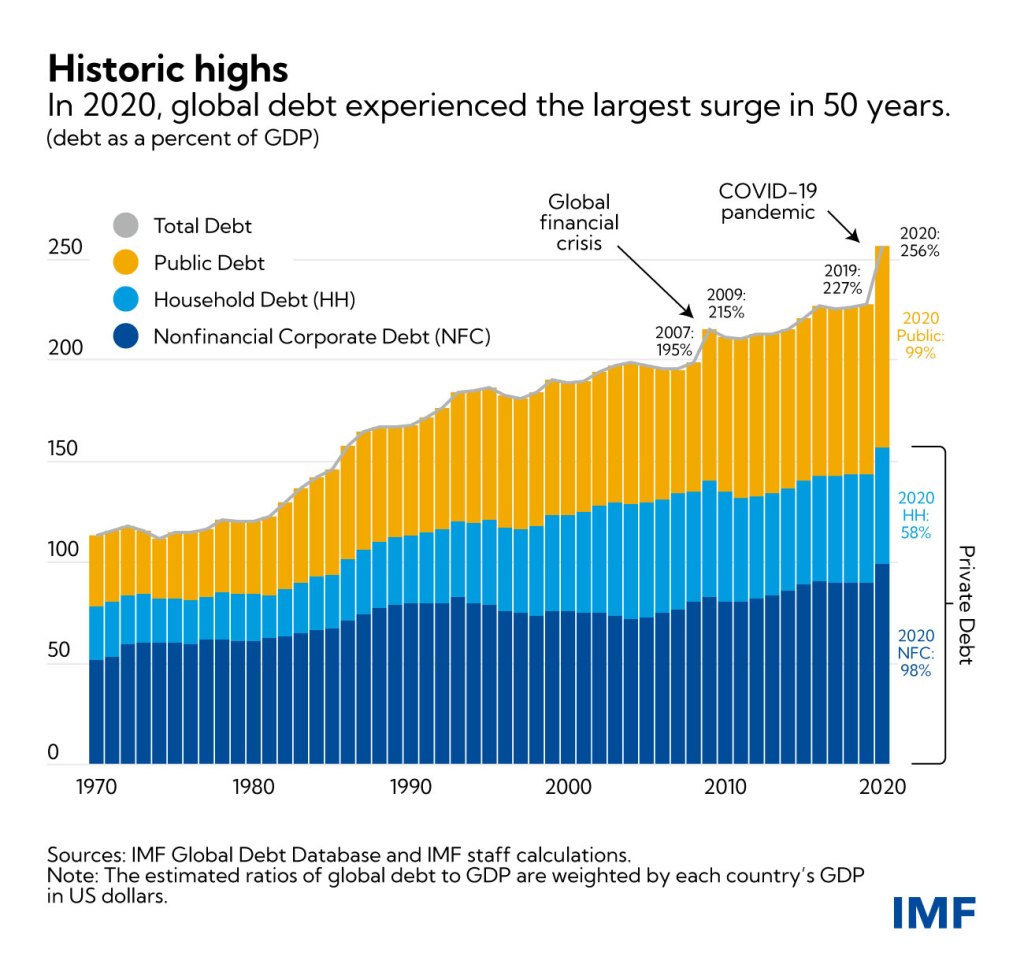

Looking back at this R2 note also reminds me of how financial expectations have shrunk. My parents (both teachers) were never rolling in money and at the same time, they were able to afford a good life and send three children to good (and expensive) schools. I can’t imagine this working today: consumer purchasing power has shrunk, people and nations are loaded up with debt. Life got more expensive. It’s easy to point to us going off the gold standard, but I think the answer is more nuanced and I do wonder how countries moving to a bitcoin standard will reign in public and private spending? If at all?

To this day South Africa still maintains capital controls limiting how much money you can take out the country (not a great way to encourage outside investment but that’s beside the point here). When we left the country in 1993, my parents had just sold their house and cashed in their pensions. They were well over the measly capital export allowance and resorted to buying high value appliances (can’t go wrong with Miele). Ultimately they took the risk: and packed cash into the suitcases and a one-way flight to Heathrow. To avoid implicating anyone my father hadn’t told us what was happening. All we knew was that he was terribly agitated when the luggage didn’t make the connection at Nice airport and was delayed by 6 hours. The next few days were spent going around to various London bank tellers and bureau de changes to convert Rands to Pounds. With today’s AML and KYC laws this would be impossible!

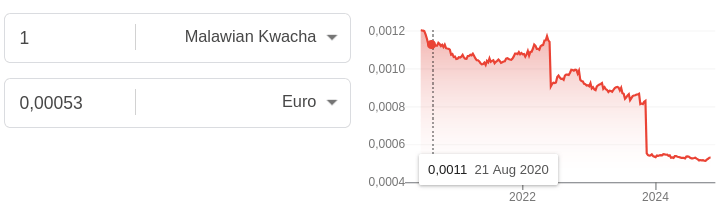

What does fill me with hope is how Bitcoin fixes these draconian capital control laws and also brings stability to those living under currencies (the other kind of shitcoins) that regularly take a 50% haircut (an Aunt lives in Malawi and recently had this happen). It’s easy to discount Bitcoin’s utility through the perspective of living on stable currencies like the Euro or dollar. But if you can’t take your money out of a country or are regularly devalued, bitcoin is valuable tool to save and move savings.

I have my late father to thanks for his early economic lessons: they helped me understand Bitcoin’s impact fairly early on. In around 2012 I was filled with new bitcoin enthusiasm and visited my cousin who at the time worked at the South African Treasury. “How lucky was I to have a contact in a competing currency provider” I thought.

I had so many questions for her about what the South African Treasury were making of this new Bitcoin system poised to take over the world: How were they planning for it? Had they bought any? Were they concerned about being out of a job.

She answered all my questions with her own: “What’s bitcoin?”

I do tend to overestimate the impact of new technology in the short term and underestimate the long term impact. Well it’s 12 years later and we see the ECB starting to wake up to these questions with some of their recent papers.

None of us can fathom the long-term impact of bitcoin; the closest we come to this is being involved in building the future.